IN NATURE’S REALM: THE ART OF GERARD RUTGERS HARDENBERGH

This exhibition was on view February 19, 2021–January 9, 2022

Morven Museum & Garden is proud to present the online exhibition of In Nature’s Realm: The Art of Gerard Rutgers Hardenbergh. Below you will find information about Gerard Rutgers Hardenbergh's life and work. To go directly to a gallery of his artwork click here. Click the image to zoom in.

Photography by Lynnette Mager Wynn unless otherwise stated. Special thanks to Stefanie Taylor for designing and compiling this online exhibition.

Table of Contents

1. Early Life & Family

2. Hardenbergh as an Ornithologist

3. Ornithology & Art

4. Life in Bay Head

5. Plates

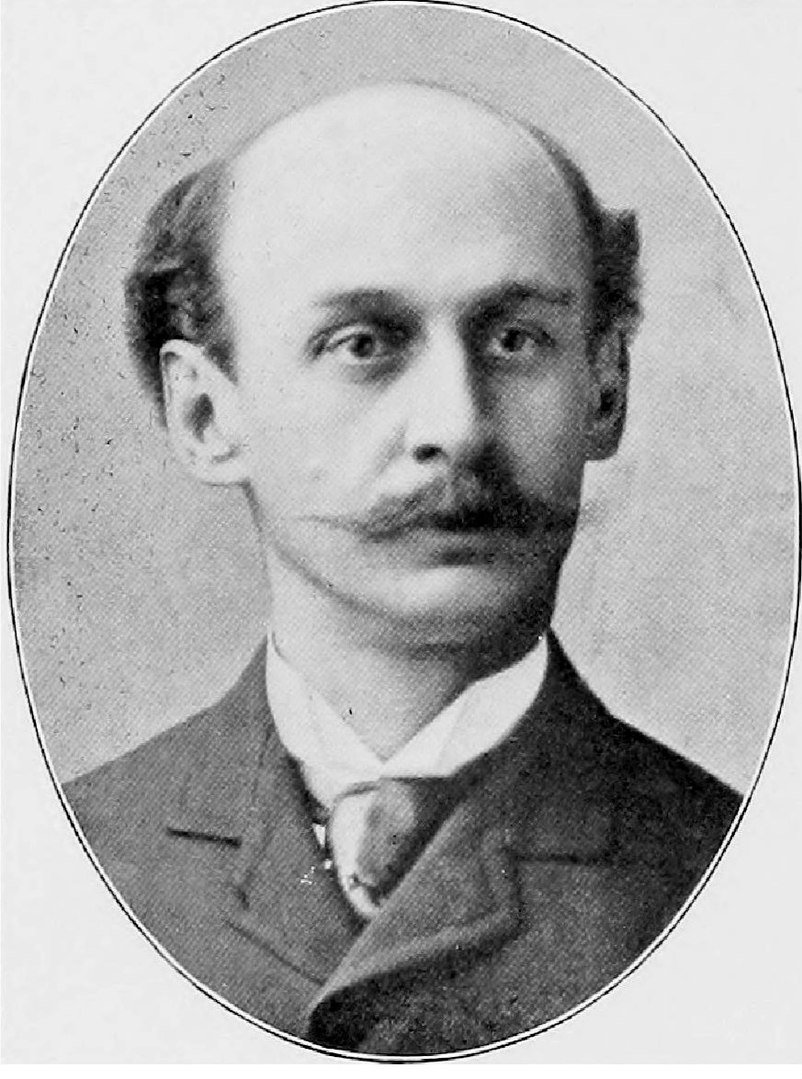

Early Life & Family

Gerard Rutgers Hardenbergh was born to Warren and Cornelia Hardenbergh in New Brunswick, New Jersey in 1856. The Hardenberghs were a wealthy family with Dutch roots dating back to the colony of New Netherland. Johannes Hardenbergh, Jr. (1670–1745) once enslaved leading abolitionist Sojourner Truth. His son, Gerard’s great-great grandfather Reverend Jacob Rutsen Hardenbergh (1736–1790), was the first president of Queens College (renamed Rutgers College in 1825).

Gerard’s father, Warren Hardenbergh (Rutgers class of 1844) was a counsellor at law and real estate agent. Gerard’s father encouraged his son’s natural interests, taking him to the Chadwick Sportsman's Hotel in Ocean County for shooting and fishing. Hardenbergh continued to visit as an adult and Chadwick House is the subject of many of his works.

While attending Rutgers College Grammar School, young Hardenbergh attended a series of lectures on birds by natural sciences Professor Samuel Lockwood (1819–1894), perhaps his first exposure to what would be a lifelong interest in ornithology (the study of birds).

Hardenbergh as an Ornithologist

Ornithology—the scientific study of birds—was not much older than Hardenbergh himself. Historically, American species of plants and animals had largely been ignored or even categorized as degenerate versions of Old World specimens. Then, beginning in 1808 Alexander Wilson began publishing his nine-volume work, American Ornithology. John James Audubon’s (1785–1851) Birds of America volumes followed from 1827 through 1838.

Through the newsletters of burgeoning ornithological clubs one can get glimpses into the work that Hardenbergh was doing in New Jersey. On December 15, 1877 W.E.D. Scott wrote in The Country, about the bird “Little Auk,” “We record with pleasure the capture of a specimen of this rare and, in this part of the country, little known species. It was driven ashore during the late severe storm, and being utterly exhausted, was captured by Gerard R. Hardenbergh, Esq., of New Brunswick, N.J., who has been for the past month collecting for us about ten miles south of Squan on the coast. Mr. Hardenbergh kept the bird alive for two days, and we were enabled in this way to get a good idea of its positions. It proved on dissection to be a female, and was in full plumage.”

In the winter of 1901, Hardenbergh also taught a series of “practical lessons upon ornithology” in Lakewood. An article described Hardenbergh as “a student whose books have been the woods and whose mentor [was] Dame Nature herself.”

Ornithology & Art

With the exposure time required for early photography and the variable success of taxidermy, highly detailed portraits of birds proved the most efficient way of study. Volumes like Audubon's were expensive and usually paid for by subscribers, mostly museums, libraries, and the wealthy. However with the improvement of lithography and chromolithography (prints with color) the study of birds became more accessible—something that Hardenbergh seems to have been interested in. Hardenbergh worked on a number of bird charts and games for public consumption and a number of his own paintings were turned into chromolithographs. These more egalitarian outlets also provided an additional source of income for a working artist.

It is not known if Hardenbergh was a self-taught artist, records of any formal training do not exist. But by the age of 20 he was exhibiting works at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. One review stated, “One sees drawings of animal life everywhere here, but none so good as the oil paintings of birds done by G.R. Hardenberg [sic] of New Brunswick. Mr. Hardenberg [sic] is only eighteen years old but is already a careful and accurate ornithologist and prominent artist."

Life in Bay Head

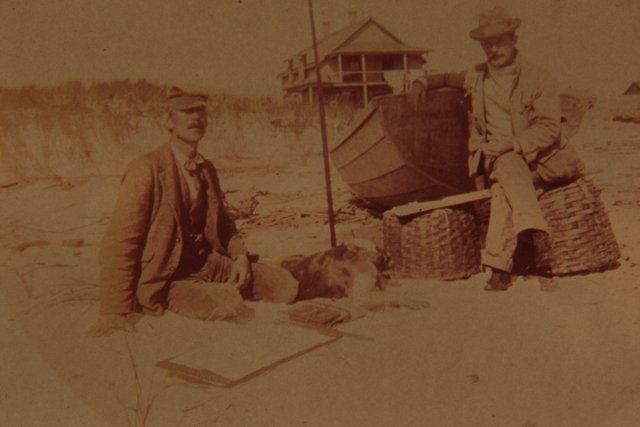

Through his adult life Hardenbergh split his time between New Brunswick and the shore. He usually kept a studio in New Brunswick, on Neilson and later George Street. Eventually Hardenbergh purchased a houseboat and renamed it Pelican. He kept it moored in Bay Ditch and other spots around Bay Head, using it as his summer house and studio. In 1904 Hardenbergh bought a house in Bay Head on W. Lake Avenue.

Two years later, Hardenbergh married Charlotte Louise Whitehead in Manhattan. Charlotte had purchased a house in Bay Head the year before. The newlyweds moved into Charlotte’s house on Lake Avenue and Hardenbergh eventually abandoned the Pelican.

Hardenbergh died nine years into his marriage, passing away in Bay Head in 1915. The Asbury Park Press remembered him as, “one of the best-known men along the Jersey shore...His life was wholly devoted to his art and his study of bird life, but he was a good companion, an entertaining host and a gentleman of the old school.”

Plates

Haviland & Company had its beginnings in New York City when it was founded by American David Haviland, initially as an importer of tableware. He opened a porcelain decoration shop in Limoges, France in 1847 and by 1855 Haviland was manufacturing and decorating porcelain in France for the American market.

While Hardenbergh designed the plate set and the designs were likely copied by artists in France. Haviland & Company also produced the White House porcelain service for President and First Lady Hayes in 1879. That pattern, depicting American flora and fauna, was created by Theodore R. Davis of Asbury Park and then executed by the Haviland workshop.

On December 14, 1894 a piece in The Daily Times (New Brunswick) described Hardenbergh’s annual art exhibition at his Neilson Street studio which included designs for some of these plates, “There are shown also a set of designs for game plates for Haviland, the famous manufacturer of china and porcelain ware. Each plate is vividly colored and contains a group of game birds in characteristic attitudes. Pen and ink sketches for Haviland and Collamore are also shown…”

This collection of plates is the only known surviving set.